BUSTED AND EVICTED

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

-First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

Seminal to America’s survival as a democracy are those forty-five soaring words.

After the Bible, they are the most cherished, hallowed words I know. But as far as the Los Angeles sheriff’s department was concerned, they might never have been written.

A confluence of behind the scenes power, its instrument the snappily uniformed sheriff’s deputies, was gathering for the destruction of His Place.

Intimidation, harassment, threats against my life, bribes, Draconian laws, and conspiracy were being marshaled against our church in an effort to drive us from the Boulevard.

I hadn’t made the Boulevard a hippie haven; the Boulevard had turned rancid before I arrived. Although I would have been as euphoric as the businessmen and the sheriff’s department to see every hippie won for the Lord and leave the area, those who should have been my friends and supported our work became instead enemies bent on destroying us.

But in the meantime I was determined to stay.

The campaign to annihilate His Place and send me packing was fierce and dirty and in my mind unconstitutional.

The first bust came while I was witnessing on the Boulevard between the Hamburger Hamlet and Mother’s, a combination pool room and coffee house. I was sharing Christ with two interested passers-by. We were standing only a foot from the wall of a building, leaving the wide sidewalk clear for uninterrupted pedestrian traffic.

“You’ll have to keep moving,” said one of the two sheriff’s deputies who approached me as my two prospects walked on with the Bibles and Gospel tracts I had given them for study.

I knew the law. The California State Penal Code, Section 647C, says a person can’t “maliciously block the sidewalk.” Since I wasn’t blocking the sidewalk, maliciously or otherwise, I refused to budge. “You have to keep moving,” the deputy said again.

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech ‘¦ or the right of the people peaceably to assemble.”

Did the vengeful no-loitering law, which was enforced no place in Los Angeles County except on the Boulevard, supersede the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States?

In my opinion, no.

In the opinion of the sheriff’s men, yes.

“You’re under arrest!” said the officer, jackknifing my hands behind my back and slapping handcuffs around my wrists.

Handcuffs as a penalty for telling people about Jesus. It didn’t seem possible. I wasn’t a homicidal maniac. A would-be presidential assassin. An escaped killer. Man, I wasn’t even a bellicose, drunken straight weaving down the street, as many do every day along the Boulevard, looking for a fight or propositioning women in the foulest language.

I was shoved into a squad car and taken to the sheriff’s lock-up, the West Hollywood County Jail.

I was searched and manhandled by a deputy. I couldn’t imagine what he was looking for. What he found were three Bibles and about two hundred Gospel tracts nothing but the word of God all over me.

The handcuffs were removed and the deputy ordered me to take off my wedding ring. I refused. He shimmied it from my finger.

The deputy and a couple of other officers standing around were aggressive, impolite, rough, and nasty. There wasn’t an ounce of dignity or even routine courtesy in their behavior.

One deputy mocked me. “You ain’t no ordained preacher. You’re just a kook and a Communist. Whoever heard of a real preacher in jail? You ought to be ashamed of yourself. The Bible says you should cooperate with the authorities and not disobey the law.”

“Man, don’t you tell me about the bible. Peter and John got busted, too.” I flipped to the Book of Acts and read aloud from 4:2-3: “Being grieved that they taught the people, and preached through Jesus the resurrection from the dead. And they laid hands on them, and put them in custody.’

“You’re the ones who should be ashamed,” I said, my anger rising. “Jesus and his first followers were all busted.” I turned to Acts 5:18. I read it loud and clear. ” ‘And laid their hands on the apostles, and put them in the common prison’.”

A deputy snatched my Bible from my hand and hustled me into a small, barred retaining section of the jail.

I asked the guard, “May I please have my Bible?” He ignored me.

I sat against the wall and began singing hymns and quoting Scripture from memory.

“Shut up,” the guard said.

In song and verse I kept singing His praises.

Exasperated, the guard came back and said, “If we return your Bible, will you shut up?”

I nodded.

And the Book was handed to me.

Soon the guard ordered me to remove my shoes, and I was transferred to a large, crowded bullpen. We were packed together like peanuts in a vacuum sealed can. There wasn’t even room to lie down.

I knew half the guys in there from the Boulevard. A doper I’d witnessed to many times called out, “Arthur, what in the world are you doing in here?”

I told him the circumstances of my arrest and then said, “I believe I’d like to preach.”

My doper pal quieted everyone down and gave me the floor. “Preacher, go ahead and do your thing.”

It was easier to reach the prisoners with the Word than it was to reach the police.

The text of my sermon was obvious: How to Be Happy in Jail. I told them they were as sad- looking a bunch as I’d ever seen, that none of them were happy except me and I was happy because I was saved. I added that by coming to the Lord they could find out what real happiness was all about.

When I gave the invitation, two prisoners stepped forward and they prayed without shame in front of everyone.

About three in the morning a teen-ager spaced out on STP was brought in and I worked with him through the night, gradually bringing him down.

I was released at noon the next day. Bill Gazzarri, the Gazzarri’s entrepreneur.

My trial was to be the initial court test of the no-loitering law. If the statute was upheld, our ministry would suffer a crushing blow since street-witnessing was crucial to our work of winning souls.

Though I had no money, my most pressing need was a first-class lawyer. I phoned several preachers and they gave me a list of twenty eminent Christian attorneys. I was assured that any one of these good, God-fearing lawyers would take my case without fee. Each would be overjoyed at the privilege of defending the Gospel.

I called every one of them a disheartening experience. The least expensive said he would charge me five hundred dollars, and that provided he had to appear in court only once.

There was no way I could raise the bread.

So I went to the Los Angeles headquarters of the American Civil Liberties Union. Without a moment’s hesitation I was told the ACLU would be honored to represent me in court because they agreed that my rights under the First Amendment had been trampled.

I asked for a Christian attorney, but was told I would have to accept whichever lawyer was available to donate his time and skill.

Martin H. Kahn was the attorney assigned to me. He was young, likable, brilliant and Jewish.

I didn’t care one whit that he was Jewish. What concerned me was that he was unsaved. “Be ye not unequally yoked together with unbelievers.” 2 Corinthians 4:14 said. That verse had been pounded into me at church, college, and seminary, and because it was in the Bible, I accepted it without question.

I wondered if a person who didn’t know Christ the way I knew Him could defend me. Could he understand my passion for the Lord? Could Jew and Christian be compatible? Martin was tremendously interested in my pending trial and eager to go into court on my behalf.

“I’m not a Christian,” he said when I told him the nature of my doubts. “But I appreciate and respect your beliefs and I believe in your right to express them. That’s why I’ve taken your case.”

I was still troubled. Everything about Martin appealed to me except that he hadn’t given his heart to the Savior.

“I think I’ll be my own attorney,” I said.

“If you want to defend yourself,” Martin replied, “I’ll help all I can. There are a lot of legal technicalities you’ll need to know. And it could get very complicated.”

I was overwhelmed by his generosity, and suddenly I was ashamed of myself. The thought of those twenty so-called Christian lawyers flashed to mind. Their attitude didn’t seem very Christian at all. Just a bunch of lawyers interested in a fee. And here was a man not getting a dime for the case and he was far more concerned with my rights than people who passed themselves off as Christians.

“Martin, my anxieties are over,” I said. “Forgive me for hesitating. I apologize for doubting you. It had nothing to do with your religion or you as an individual. It was just something I had to battle in my mind. I had to decide if I could be defended in court as a Christian evangelist and minister by someone who hasn’t had a conversion experience.”

“I understand,” Martin said, his face breaking into a huge smile. We shook hands and prepared to do battle.

The trial testimony of the sheriff’s officers virtually destroyed the last small hope I had in police integrity. Incredibly, the deputies testified that a crowd varying in number between 30 and 150 had gathered around me at the time of my arrest! That was as far from the truth as the sun is from the moon.

In his cross-examination of the deputies Martin didn’t dispute the size of the alleged crowd. He went right to the heart of the issue, drawing from the deputies the admission that pedestrians were able to navigate the street, that I hadn’t prevented the free movement of anyone, that I was not in fact blocking the sidewalk.

The charge against me was so weak that Martin didn’t trouble to put me on the stand. In view of the deputies’ testimony that I wasn’t blocking the sidewalk, he asked the judge for a dismissal.

The judge said that whatever the size of the supposed crowd there was no evidence introduced that I held or forced anyone to listen to me, that foot traffic had not been impeded, and that no pedestrian had made a complaint.

“The case is dismissed,” the judge declared.

I was elated with the verdict, but it proved a short lived victory. Our street ministry and the survival of His Place were still threatened as the sheriff’s department stepped up its intimidation. Without search warrants they swept through His Place almost every night, checking kids out and indiscriminately arresting many of them. Those arrested were innocent of any wrong doing. They were taken to headquarters, questioned, and released.

The culmination came on a night when His Place was raided three times! The sheriff’s men fanned through the building, saying they were looking for runaways, curfew violators, and kids without proper I.D.’s.

“In your patience possess ye your souls,” Luke wrote in 21:19.

Yet patience would play directly into the hands of those who wanted us off the Boulevard.

A line had to be drawn. A stand had to be made. Prayer had to be reinforced by action.

I walked to the commander of the sheriff’s raiding party and said, “Sir, I’m placing you under citizen’s arrest. I charge you with illegal search and seizure and trespassing.” “Shut up,” he spat out. “We’ll come in here anytime we want.”

“No! Not unless you have a search warrant or a plausible reason. Your men use profanity. We have a rule that says no guns are permitted in God’s house. Your men are wearing guns. You are welcome to come in, take a Bible, and pray. Otherwise, this is a private building, and you are not permitted in here.”

“You’re just harboring degenerates, dope addicts, and pushers,” he said. “The scum of the Boulevard.”

“If you catch anyone dealing on our premises, arrest that person and make a specific charge. What you’re doing is persecution, no different from Communist Russia or Nazi Germany.”

I asked for his name and badge number, but he laughed and walked out the door where a flotilla of squad cars were parked. A stranger would have thought we had a hundred Jack the Rippers inside the building.

Completely fed up, I decided to pursue my constitutional guarantee of freedom of religion. Quicker sought than found, I rapidly discovered.

I went to the sheriff’s department and attempted to consummate my citizen’s arrest against the officer who had led the raid. The deputy I talked to wouldn’t even give me the form to fill out. He said the department wasn’t in the habit of accepting charges against its own men who were merely carrying out orders. He told me to take my complaint to the district attorney.

I called Los Angeles County District Attorney Evelle Younger, but I couldn’t get through. His chief assistant said in any case there was nothing that office could do.

I phoned the Civil Rights Commission in Washington, D.C.

“It’s not within our jurisdiction.”

“Sorry.”

I called the U.S. Marshal’s office in Los Angeles. I was told to call the U.S. Attorney, who told me to call the FBI, who told me to call County Supervisor Debs. (“You’re running a hog wallow down there. Anything the sheriff’s office wants to do to clean up the mess on the Boulevard, I am for,” he said smugly.)

I called Governor Ronald Reagan. His office told me to call Senator George Murphy. Senator Murphy’s office brushed me off.

I called Senator Edward Kennedy’s Washington office and got my first and only polite, sympathetic hearing. Senator Kennedy was out of town making a speech, but one of his aides said he would be willing to investigate the matter, though it should more properly be dealt with through my own congressman.

I called my congressman and several other Southern California representatives. None of them was interested.

It all added up to one long merry-go-round ride with no brass ring.

I again took my complaint to the ACLU. Yes, they would go to court on my behalf.

But courtroom action might take forever. And even if I won a verdict in court, His Place might no longer be in existence by then. If the sheriff kept raiding us, the kids couldn’t come and any hope I had of reaching them for Christ would be lost.

I gathered the staff and told them we were going to stage a demonstration, a demonstration for freedom of religion. It was a spur-of-the-moment idea.

We asked that night’s His Place crowd, about two hundred kids, to join the demonstration. With the exception of a few who were totally spaced out, everyone volunteered. If we had planned the demonstration, passed out handbills, and held back for a week we could have raised an army of thousands of kids. But I decided to go with those on hand. I was anxious to bring the issue directly to the doorstep of the sheriff.

We quickly rounded up a couple of walkie-talkies and a bullhorn, and assigned monitors to keep the crowd in check and make certain there was no violence or disobedience of the law.

We met in front of the Classic Cat, which featured girls. Tiny Joel held up his sign: “POLICEMEN, WHAT’S WRONG WITH MY DADDY?” Mine read, “WOULD YOU ARREST JESUS FOR LOITERING?”

A sheriff’s squad car rolled up and a deputy asked me to call off the demonstration. “You’re supposed to be a Christian, and you’re having a demonstration.”

“There’s nothing un-Christian about a demonstration. This is for Jesus.”

We marched up and down the Boulevard for two or three hours, being careful not to block the sidewalk and obeying the traffic lights. Then we massed in the parking lot of the Sheriff’s Department.

Waiting for us were hundreds of officers, all with guns

.

I got on the bullhorn and explained why we were there, and I preached the Gospel. Several kids who’d been saved at His Place gave their testimony. Soon the crowd started chanting: “We want to talk, we want to talk, we want to talk.”

But no one from the sheriff’s office would meet with us. The officers stood firm. When I heard some of the kids shout “Pig,” a term for the police I despise, I decided to break it up. Both sides were getting edgy and tense. I led the crowd back to His Place.

The news of our demonstration was broadcast over radio and television and for our second peaceful protest more than three hundred kids turned out.

Again we massed in the sheriff’s parking lot. Again the “We want to talk” chant went up.

A deputy finally emerged and said they would meet with three of us. I went in with one of my staff members, Barry Sparks, and a friend named Barry Woods.

We talked with the sheriff’s community relations officer. The meeting was short and to the point. He would make no concessions, no direct promises that the department would stop hassling His Place.

“I’m going to call this demonstration off,” I said. “But I want you to know that if your men ever raid our church again without a search warrant or proper cause I’m going to organize the biggest demonstration in the history of Sunset Boulevard. We’ll blow the lid off in the name of Christ.”

I went outside and dispersed the crowd.

The next day I got a call from the ACLU’s Bruce Margolin. He said he was prepared to file a restraining order against the sheriff plus charges of assault and disturbing the peace. Bruce said I was also in a position to file a personal damage suit for $100,000 for defamation of my name, character, and reputation.

I told him to hold off. I wanted to see how the sheriff’s department would react now. I had no interest in a courtroom vendetta if it could be avoided.

The demonstration tactics worked. His Place was never rousted or raided again. The sheriff’s men came by from time to time and if they had a justifiable reason for entering we gave permission without a warrant.

But now they were always polite!

Although His Place at the last had become an acknowledged sanctuary of God, the streets of the Boulevard were still a battleground. I had to be free to witness anywhere, anytime, as Jesus did. I considered street-witnessing as important to our ministry as His Place and the Halfway House. The timorous, the troubled, the suspicious could often be reached in no other way. Some of the most gloriously saved Christians I knew had their first interest in Christ generated in a sidewalk contact. The Lord doesn’t mind where a soul is won. He offers salvation and everlasting life to those who come to Him in a church, a stadium, a nightclub, skid row, a jail cell, the private office of a corporation executive, as well as the sidewalk. The paramount consideration is leading the lost to Christ wherever contact can be made. And the sidewalks of the Sunset Boulevard offered abundant opportunity for such contacts.

My acquittal under 647C had in effect destroyed that statute in the State Penal Code. But the ever-resourceful county had passed a fresh, equally obnoxious law, Ordinance No. 9648.21, which said: “A person shall not loiter or stand in or upon any public highway, alley, sidewalk or crosswalk or other public way open for pedestrian travel or otherwise occupy any portion thereof in such a manner as unreasonably to annoy or molest any pedestrian thereon or as to obstruct or unreasonably interfere with the free passage of pedestrians.”

The italicization of the adverb “unreasonably” is mine. Could a minister unreasonably witness on a public sidewalk as long as he did not “annoy or molest” or use force? Could the Bible be unreasonably quoted to an interested passer-by who chose of his own accord to listen?

The answers to those questions were as obvious to me as the answer to the question: Does God exist?

What was unreasonable was the broad, free, and easy enforcement of the ordinance, which was only the old law dressed in new verbiage. It was simply another power play to drive the young people from the Boulevard. The Establishment had not yet learned its lesson.

I collided head-on with the new ordinance while I was standing against the wall of the Hamburger Hamlet with a friend, the Reverend Mitchell Osborn, education director of the Highland Avenue Baptist Church of National City, just outside San Diego. Mitch had come up to help me witness on the Boulevard, and we were passing out Gospel tracts when the inevitable sheriff’s men arrived. Said one, “You’ve got to move.”

“We are not obstructing pedestrians. You can see the sidewalk is clear.”

“Are you going to move, or are you going to be arrested?”

“I hate to have such a choice. But since we are doing nothing wrong, we are not moving.”

The deputy busted me, ringing my wrists once more with handcuffs. Looking at Mitch, he said, “Do you want to go, too?”

“Might as well,” said Mitch. He was also handcuffed.

In less than thirty minutes I was back in the bullpen and preaching again. Two of the inmates were brought to the Lord as the result of our jail service.

After twenty-four hours in the sheriff’s bullpen we were transferred to the big county jail downtown. They lined us up about a dozen prisoners all in handcuffs with a chain running through the cuffs from man to man, binding us all together.

I sighed and took it in stride. Nothing the sheriff’s men might do would surprise me. But I felt burdened for Mitch. He was a straight and a conservative minister, nothing hip about him. A graduate of Golden Gate Theological Seminary and the California Baptist College, Mitch had a wife, two children, and a passion for winning souls. This was the first time he’d ever been arrested. I don’t believe he ever had so much as a traffic ticket before.

The police van gave us a wild ride downtown. The driver, his foot pushing the accelerator to the floor, was purposely making it uncomfortable for us, taking the corners on two wheels, jostling all of us in the back of the van. The handcuffs were so tight my wrists were beginning to bleed. Through it all, I tried to witness to the fellow sitting next to me.

“Man, I don’t feel like hearing it,” he said. “Will you please leave me alone?”

At the jail we were stripped, shoved through a cold shower, deloused (presumably), fingerprinted and photographed, and moved into a cell, the whole dangerous convict bit.

I suddenly remembered that I was scheduled to preach in a few hours at the Mount Zion Baptist Church in Watts, the largest African American Baptist church in the West. And here I was in jail.

Unexpectedly, a deputy came up to our cell and said we were free to go. Mitch’s wife had bailed him out. My bail money came from a highly unlikely, unexpected source, my old friend Richard, the pusher who had given His Place one of its more memorable episodes the night he outsmarted the sheriff’s men by pretending he was a narc.

I ran home, changed and zipped out to the church in Watts. Man, it was a powerful service. I preached about my getting busted and hassled by the police, and those were facts of life that everyone in the Watts ghetto thoroughly understood. Amens soared through the air like angels.

News of my latest arrest hit the papers and the TV and radio newscasts. The ACLU called, asking to represent me. This would be the first court test of the new ordinance.

Another extraordinarily gifted Jewish attorney volunteered his time and skill, cost-free. All my attorneys have been Jewish. Only too aware of the terrible price that has been paid for the right to worship freely, these men are in the forefront of the struggle to guarantee the sanctity of the First Amendment.

When we went to trial, my attorney, Bennett Kerns, challenged the law on grounds that it was, on its face, unconstitutional.

The jury was composed of upper-middle-class straights from Beverly Hills, Bel-Air, Brentwood, Westwood, Santa Monica. They were all over-forty Gold Coast Establishmentarians. How could they understand my work with young people whose life-style and values conflicted so starkly with their own? I would have appreciated at least one under-thirty long-hair in that jury box.

However, there was no cause for concern. Bennett destroyed the prosecution witnesses, and after all the evidence had been heard Mitch and I were acquitted. And the jury’s verdict was unanimous!

Coincidentally, that day I was scheduled to speak before the well-fed, well-entrenched sachems of the West Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. When the invitation had come, I was surprised beyond words. But the Chamber’s program chairman was an eminently fair man. A spokesman for the sheriff’s department had addressed the group and given a vehement antihippie speech. Now the Chamber wanted to hear an opposing view.

Four representatives of the sheriff’s department, including the West Hollywood station commander, were in the audience. I felt like a lamb in a lion’s lair.

The Chamber president, prior to my talk, made an announcement that the group had just raised a sizable amount of money for the support of blind children.

This gave me the springboard for my message. There was so much to say. I had been wondering how I could extract the essence of my position in a short talk.

“I commend you for your contribution to the blind,” I began. “But what about the thousands of walking blind who pass your business establishments every day and to whom you so heartily object?”

“These are the blind who have eyes but do not see. They need direction, someone to show them the light so they might see for the first time in their lives, someone to bring them hope, strengthen their souls.

“Sure, they’re kids hung up on the needle and pills. But how many in this room have sons or daughters strung out on drugs? It seems so easy to condemn a kid who’s rejected his parents until one of your own children becomes a runaway. And if he runs away to a strange city, who will be there to help him?

“When you think about that your condemnation of the young people of the Boulevard must be mixed with a little compassion.

“It’s not only the kids on the Boulevard who are blind, but many adults who come out of your fancy restaurants staggering and blind drunk.

“What difference is there between a kid blinded by speed, acid, or pot and a businessman blinded by Scotch, bourbon, or vodka?

“The generation of the young and the generation of straights both must come to God and live for Him.

“I ask every businessman in this room: Are you blind to your responsibilities, your responsibilities to God and your fellow human beings?

“I ask you: What should really count on the Boulevard, the dollar or people?

“Why have I had to fight tooth and nail for the survival of my church, a church where many of the blind have been taught to see? Why have I been arrested for preaching on the sidewalks the same message of Christ you hear in your own churches on Sunday mornings?

“I leave the answers to your own consciences.”

I sat down. Had I convinced the alliance of businessmen and the sheriff’s representatives to take the pressure off the kids, off His Place, off my witnessing in the streets? Was all the hassle over at last?

I didn’t have to wait long to find out. In eight hours I knew. In eight hours I was busted again.

About ten o’clock that evening I was in front of the Sunbeam Market witnessing to a young doper known as “Trip,” a fitting cognomen. He swallowed acid like jelly beans.

“When are you going to start tripping out on Jesus?” Trip shrugged.

I began to share Christ with him. If ever a soul needed Christ, Trip did. Only in his early twenties, the dissipated countenance, unhealthy pallor, and emaciated body so often seen in hard- core addicts made him look twice as old.

A sheriff’s car drove up.

“Keep moving,” a deputy shouted.

I was stunned with disbelief. It couldn’t be happening again.

At the sight of The Man, Trip took off like an Apollo rocket. I was alone on the sidewalk. I stood there, unmoving.

The deputy scrambled from the squad car and said belligerently, “Are you going to move or not?”

“Officer, don’t you know I won this thing in court only this morning?”

“I’m under orders to keep everybody walking. Now walk or else!”

“I have my orders, too from God, and He says I should stay here and witness. As you can see, I’m not obstructing traffic.”

Out came the handcuffs. Manacled again. Busted for the third time. Though I put up no resistance, the deputy shoved me hard against the steel exterior of the squad car.

When Bennett Kerns heard of my new arrest, he nearly split a gut. We agreed there could be no reason for the continuing arrests other than harassment.

At the trial we introduced testimony that the sidewalk was thirteen feet wide, making it impossible for one person to obstruct it.

Two ladies on the jury went down to the Sunbeam Market and measured the sidewalk. Their figure tallied exactly with ours.

I was not only swiftly acquitted, but every member of the jury stepped up and congratulated me. Several said they were in favor of my work. One well-dressed matron told me, “It’s humiliating and disgraceful that you were even brought to trial.”

Three trials. Three acquittals.

Unless the county now passed an ordinance outlawing breathing on the sidewalks of the Boulevard, perhaps I could safely assume I was free to continue my street-witnessing.

Then came the most punishing blow of all.

Two days after my third acquittal, my landlord notified me that he would not renew the lease on His Place!

The pressures against him were not to be believed. There had been a meeting among the largest property owners on the Boulevard and an agreement struck that no one would rent to any business catering to teen-agers, His Place included.

The straights were hurting. His Place had put a neighboring liquor store and nightclub into bankruptcy. Other businesses in our immediate area threatened a rent strike until His Place was closed.

My landlord was visited by sheriff’s representatives and encouraged not to renew my lease.

All of this was a last-ditch attempt on the part of the Establishment to sweep the Boulevard clean of hippies and turn it back into a happy hunting ground for straight drunks.

But though His Place might vanish like a vapor that didn’t mean the hippies would disappear. In fact, we were the only ones effectively weaning the hips off the Boulevard. Some kids had been busted a dozen times by the sheriff and warned to keep away from the Boulevard, yet they returned like homing pigeons.

I visited my landlord, an elderly, wealthy man free of malice and completely in accord with my work.

“I like you,” he said. “I know you’re doing a good job, but I just can’t stand the pressure. I’m an old man and I don’t want problems. I want to live in peace. Everyone’s on my neck because I rent to you. I’ve even had calls threatening my life if I let you stay in the building.”

On the floor of his living room I fell to my knees at his feet. I begged without shame. “You can do so much to help people and help God’s word. Please, please don’t put us out.”

Gently, the landlord said, “I’m sorry. I just want peace.”

The news that His Place was closing spread rapidly along the Boulevard.

Our final days in the building inevitably arrived. A few moments before the midnight deadline for vacating, I preached and told the large crowd, “His Place is not closed, only temporarily

transferred.”

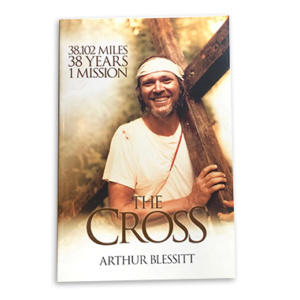

The last thing we did was unbolt our cross, which by now had become the symbol of His Place. I hefted it to my shoulder, went through the door and marched down the Boulevard, a public declaration that I had no intentions of silently folding our tent and disappearing.

We moved His Place into a street, re-gathering our church in the parking lot of a dry cleaning establishment. The owner had given us permission to use his property at night after he closed.

We were still witnessing, praying, helping to save souls, still serving Bibles, tracts, Kool-Aid, coffee, bagels, and sandwiches.

During the day I hunted for a building. Many were vacant, but none were available to me if using my own name. I phoned an owner or a real-estate office and expressed interest in renting an empty building, the answer was always no. To prove collusion, I would have members of the staff call back without identifying themselves as my associate. The answer was always that the building was for lease.

Our parking lot ministry lasted a month. Then Bill Harris managed to rent a building in his name, which he sublet to me.

We moved down the street from 9109 Sunset to 8913 Sunset.

The new His Place flourished as never before. Our crowds were running from five hundred to two thousand a night. We had no problems with the sheriff. But then the complaints began rolling in from the landlord we were violating the building rules by bringing “degenerates” into the area; His Place was offensive to the neighboring establishments and not in harmony with the surrounding area.

We certainly weren’t in harmony with the surrounding area His Place had no dancers, we didn’t serve booze, we didn’t permit pushers to deal their wares.

Unharmonious too was the fact that at His Place the cross, not the cash register, was our guiding light.

We were at our second location only two months when the eviction notice came. We went to trial and lost.

Because there was no other choice I then made the decision to chain myself to the cross.